This year marks Sherbro Foundation’s 10th anniversary, bringing back a flood of memories. Few are as vivid or became as important as the Orchards for Education, below 2023.  I traveled to Sierra Leone for two years before founding Sherbro Foundation. It was back then that Paramount Chief Charles Caulker told me the story of his baby tree he dearly loved. A coconut tree was planted together with his umbilical cord in his mother’s village at the traditional naming ceremony. After about ten days when it’s clear the newborn will survive, it is presented to the community and their name proclaimed. Baby Charles was named after UK’s Prince Charles, born the year before. Below, a naming ceremony I attended for two newborns in Rotifunk  After weaning, two-year-old baby Charles was sent to live with his maternal grandparents in their village until he started primary school, a traditional practice. His grandfather taught him to water his coconut tree and take care of it. The small child could see his tree growing as he did in his first few years. It was an early lesson for children in valuing trees and caring for the environment. When he later returned on school holidays, Chief Caulker said the first thing he wanted to see was how his coconut tree had grown and to learn to climb it like the village boys. I heard this story sitting with Chief under grapefruit trees his father had planted over 40 years before. It was a miserably hot day, when the sweat trickled down your back just sitting still. Chief took me to the grapefruit grove to escape into the shade. Kids climbed the trees and we ate grapefruit they dropped down that were still sweet and delicious.  Chief reminisced about his uncle saying, if you take care of a tree, the tree will take care of you years later. It will provide fruit you can eat and sell for money to live on. Chief Caulker, above, among coconut tree seedlings in today’s tree nursery. He then lamented that the tradition of planting trees for babies was lost during the war. Today, those trees could be providing money for parents to send their children to school, he said. It was that hot afternoon under the grapefruit trees in 2013 that we decided we would start partner organizations to send girls to school and grow fruit orchards to later self-fund chiefdom education programs. Fast-forward to 2023 and Orchards for Education are reality. I had the pleasure in February of sitting under the shade of coconut, lime and guava trees towering over us we planted nearly six years ago. Here’s a look at how the Orchards for Education came to be. The very first grant newly formed Sherbro Foundation made to its new partner CCET-SL in 2013 was $600 to start a fruit tree nursery. Ebola brought the project to a halt in 2014, but we resumed growing fruit tree seedlings as soon as we could in 2015. All trees in the orchard program have been grown in the nursery from seed of local fruit.  The tree nursery, above, consists of simple pergolas made of bamboo lashed together. Palm fronds are added on top for shade in the dry season. This nursery has grown 30,000 tree seedlings over the years: coconut, orange, lime, grapefruit, guava, avocado, African plum, cashew, soursop and recently, cacao. Some Malaysian oil palm were gifted.  Chief Caulker, left, plants a lime tree seedling in 2017. Chief Caulker, left, plants a lime tree seedling in 2017. Over five years, sixty acres of orchards were developed, fifteen acres at a time. Land is first manually cleared and one to two-year-old tree seedlings are planted in grids of 60 to 100 trees per acre. Bumpeh Chiefdom is lowland tropical rainforest with a distinct four-month dry season, hot with no rain. Tree seedlings must be hand-watered for 2 -3 years until their roots are established. Then they flourish.  CCET-SL Director, Rosaline Kaimbay and Arlene, above, with a coconut tree one year after planting. In the early days, there was room to intercrop between young trees. Newly germinating corn is seen here. At three years, trees are well established. Chief Caulker and Arlene, below, admire three-year-old coconut and lime trees reaching their height and more.   In tropical rainforest climate, everything wants to grow. Trees have a huge growth surge in the rainy season – as do the weeds! Workers spend weeks manually cutting back weeds three to four times a year, as well as watering young trees. Cut weeds become a natural mulch and add to soil fertility. In tropical rainforest climate, everything wants to grow. Trees have a huge growth surge in the rainy season – as do the weeds! Workers spend weeks manually cutting back weeds three to four times a year, as well as watering young trees. Cut weeds become a natural mulch and add to soil fertility. We’re proud the orchards created jobs for 21 full-time workers and one hundred part-time seasonal workers. Growing fruit trees to maturity takes patience. It’s a labor of love and the reward is worth it. Below, five years after planting, coconut trees are clearly thriving.  Five and a half year-old lime trees, below, tower over Arlene and friend. They’re the first trees to fruit.  In 2023, the first trees reached mature fruiting stage: lime and guava. Pineapples, plantain, bananas and cassava are also being grown as two-year crops. For now, early fruit income is limited and goes into paying orchard operating costs. It took five years to plant all 60 acres of orchards. Many trees take 7 – 8 years to mature. It will be about thirteen years from first planting to full maturity of all 4500 trees. The first coconuts planted will take another 2 – 3 years to fruit. But coconuts will be the biggest money-makers and keep fruiting for an estimated 20 years. |

I asked Chief Caulker, left, how he felt now that it’s ten years since we embarked on his dream of Orchards for Education. “I’m proud!” he exclaimed.

“We’ve exceeded my early expectations despite the challenges of climate change with more heat and limited water access. Agriculture is a risky business. But we’ve done well and we’re well on our way to our goal of educating our children ourselves.”

We must thank the Rotary Club of Ann Arbor for helping Chief Caulker realize his vision for the orchards. They took the lead in sponsoring two Rotary global grants of two years each to start the orchards. They organized 19 Rotary clubs in the US, Canada and India who contributed to the grants.

Fifteen of the sixty acres of orchards are designated to provide fruit income for indigent health care in Bumpeh Chiefdom. Thanks go to the Wilmington, N.C. Rotary Club, who were partners in the grant and raised funds for this part of the orchards.

Sherbro Foundation donors also contributed to the Rotary orchard grant. With matching from the Rotary International Foundation and district Rotary funds, those donations grew to cover about 25% of the project. Thank you!

I’m now like the young Charles Caulker. Every time I visit Bumpeh Chiefdom, the first thing I want to see are “my trees.” With each year, I’m seeing the orchards growing the future of their children’s education right before my eyes. The dream is reality.

— Arlene Golembiewski

Executive Director

Visit our website Donate – Thank You!

Contact Us: sherbrofoundation@gmail.com

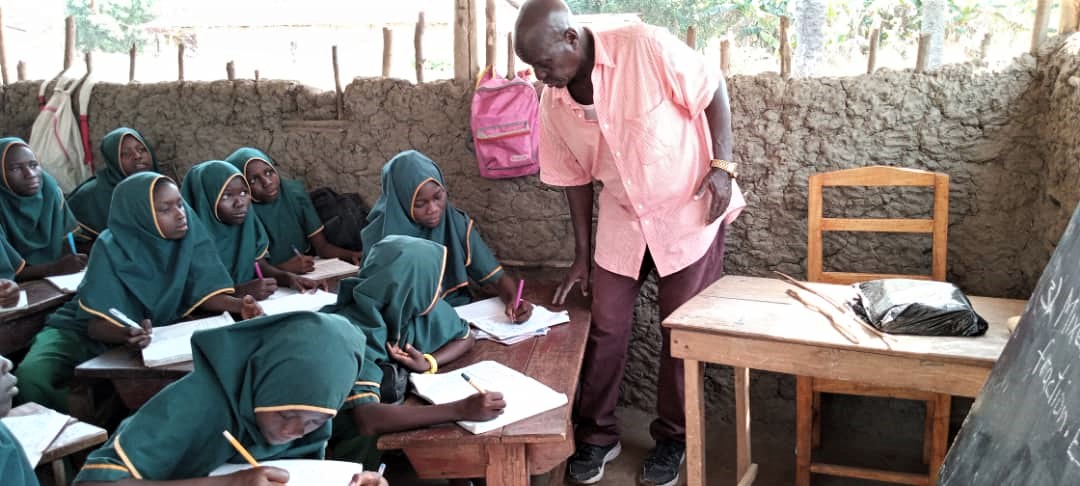

Ibrahim Bangura, left, waited a long time for his opportunity to get a bachelor’s degree in science education. Far too long. He qualified for university 18 years ago, soon after Sierra Leone’s rebel war ended. But he lost his father while in primary school, and his mother as a small market trader couldn’t help him.

Ibrahim Bangura, left, waited a long time for his opportunity to get a bachelor’s degree in science education. Far too long. He qualified for university 18 years ago, soon after Sierra Leone’s rebel war ended. But he lost his father while in primary school, and his mother as a small market trader couldn’t help him. “All this while I have been doing community teaching, teaching mathematics and physics,” Ibrahim told me. “So, I have taught pupils at senior high who are now graduates in the fields of medicine, engineering, as well as professional teachers within science.”

“All this while I have been doing community teaching, teaching mathematics and physics,” Ibrahim told me. “So, I have taught pupils at senior high who are now graduates in the fields of medicine, engineering, as well as professional teachers within science.” Tamba Kemoore Gborie is another MMTU student awarded a scholarship. He attended the Bo Government Secondary School, one of the oldest boys’ high schools in the country, and one of the few offering the full science curriculum. From there, Gborie said, “I started growing my love for science subjects.”

Tamba Kemoore Gborie is another MMTU student awarded a scholarship. He attended the Bo Government Secondary School, one of the oldest boys’ high schools in the country, and one of the few offering the full science curriculum. From there, Gborie said, “I started growing my love for science subjects.” A young woman from Rotifunk started medical school this fall with our third Saa Chakporna scholarship. Aminata Kanu completed two years of premedical science courses at the University of Sierra Leone and was admitted as a full medical student.

A young woman from Rotifunk started medical school this fall with our third Saa Chakporna scholarship. Aminata Kanu completed two years of premedical science courses at the University of Sierra Leone and was admitted as a full medical student. Another Rotifunk resident is pursuing primary care medicine as a community health officer. Gibril Bendu will be at the front line of health care when he completes his degree funded by the Sherbro Foundation board.

Another Rotifunk resident is pursuing primary care medicine as a community health officer. Gibril Bendu will be at the front line of health care when he completes his degree funded by the Sherbro Foundation board. We anxiously await Tommy Sankoh finishing his degree in agricultural economics at Njala University. With his return to Rotifunk, he’ll advise CCET-SL on its agriculture program and teach high school students and local farmers improved growing techniques and developing farming as a business.

We anxiously await Tommy Sankoh finishing his degree in agricultural economics at Njala University. With his return to Rotifunk, he’ll advise CCET-SL on its agriculture program and teach high school students and local farmers improved growing techniques and developing farming as a business.

Rotifunk, the chiefdom’s headquarters town, was typical in seeing only about 30% of teens make it to junior high.

Rotifunk, the chiefdom’s headquarters town, was typical in seeing only about 30% of teens make it to junior high.

When his father died, Kamiru, left, waited three years after graduating high school before the CCET-SL program was available to help him repeat the WASSCE exam.

When his father died, Kamiru, left, waited three years after graduating high school before the CCET-SL program was available to help him repeat the WASSCE exam.

Sometimes a principal just hands new teachers a book and sends them to a class to teach. The principal often teaches full time themselves and has little time to monitor or coach a young teacher.

Sometimes a principal just hands new teachers a book and sends them to a class to teach. The principal often teaches full time themselves and has little time to monitor or coach a young teacher.

Too often these young impressionable students see the opposite – young people who dropped out of school and with the little money they earned bought cheap cell phones and flashy clothes.

Too often these young impressionable students see the opposite – young people who dropped out of school and with the little money they earned bought cheap cell phones and flashy clothes.

Today, Kadiatu, left, is in the first group of teachers Sherbro Foundation is returning to school to pursue their HTC – the Higher Teacher’s Certificate.

Today, Kadiatu, left, is in the first group of teachers Sherbro Foundation is returning to school to pursue their HTC – the Higher Teacher’s Certificate.  Salamatu, left, another scholarship recipient, was born and raised in Rotifunk, and has been a primary school teacher there for nearly 20 years. We didn’t know just how important – and urgent – it was to open the door to higher education for her with a scholarship right now.

Salamatu, left, another scholarship recipient, was born and raised in Rotifunk, and has been a primary school teacher there for nearly 20 years. We didn’t know just how important – and urgent – it was to open the door to higher education for her with a scholarship right now.

Salamatu’s story as a teacher goes back 25 years.

Salamatu’s story as a teacher goes back 25 years.

Over six years, Sherbro Foundation sent over 800 Bumpeh Chiefdom girls to school with scholarships, most with repeat scholarships.

Over six years, Sherbro Foundation sent over 800 Bumpeh Chiefdom girls to school with scholarships, most with repeat scholarships. If fortunate to finish high school, most graduates need to earn an income right away. They start teaching straight out of high school, sometimes as a primary school teacher.

If fortunate to finish high school, most graduates need to earn an income right away. They start teaching straight out of high school, sometimes as a primary school teacher. Aziz is applying for one. He’s been teaching for seven years. Aziz was born in Mogbongboto, a small village deep in Bumpeh Chiefdom near where the Bumpeh River opens to the ocean. His parents were subsistence farmers, living off the land. He is one of twenty children his father gave birth to. His family can’t offer any financial help to further his education.

Aziz is applying for one. He’s been teaching for seven years. Aziz was born in Mogbongboto, a small village deep in Bumpeh Chiefdom near where the Bumpeh River opens to the ocean. His parents were subsistence farmers, living off the land. He is one of twenty children his father gave birth to. His family can’t offer any financial help to further his education. “At first I never want to be a teacher looking at the way the profession is neglected,” Aziz commented last year. “Later on I take it as a job. And now it’s becoming my profession.”

“At first I never want to be a teacher looking at the way the profession is neglected,” Aziz commented last year. “Later on I take it as a job. And now it’s becoming my profession.” “CCET-SL works to compliment the government’s Free Quality Education program,” Chief Caulker, left, said. “One thing the government is not able to do now is send teachers back to school to develop strong teaching skills. It’s right for CCET-SL to step in and help our own teachers. We’ve tailored teacher training scholarships for our needs and to serve as a tool for developing our chiefdom.”

“CCET-SL works to compliment the government’s Free Quality Education program,” Chief Caulker, left, said. “One thing the government is not able to do now is send teachers back to school to develop strong teaching skills. It’s right for CCET-SL to step in and help our own teachers. We’ve tailored teacher training scholarships for our needs and to serve as a tool for developing our chiefdom.”

Ms. Conteh-Morgan, right, with Chief, far right, continued, “It’s not easy for someone to rule for 35 years without his people rising against him.”

Ms. Conteh-Morgan, right, with Chief, far right, continued, “It’s not easy for someone to rule for 35 years without his people rising against him.” Amateur “devils” entertained the gathering crowds, as people found their seats under temporary shelters of bamboo and palm to escape the sweltering tropical sun.

Amateur “devils” entertained the gathering crowds, as people found their seats under temporary shelters of bamboo and palm to escape the sweltering tropical sun. The conchama, above, took the lead. She is a special sub-chief in Bumpeh Chiefdom and one of the stalwart keepers of its oldest traditions. The conchama has been a female chief for as long as anyone can remember, and is unique among women. She was initiated into Poro and participates as a leader in the men’s society.

The conchama, above, took the lead. She is a special sub-chief in Bumpeh Chiefdom and one of the stalwart keepers of its oldest traditions. The conchama has been a female chief for as long as anyone can remember, and is unique among women. She was initiated into Poro and participates as a leader in the men’s society. The day was a mix of the traditional and the contemporary, just like the man himself.

The day was a mix of the traditional and the contemporary, just like the man himself.

Some of the strongest praise came from the man who actively opposed Chief in that paramount chief election 35 years ago.

Some of the strongest praise came from the man who actively opposed Chief in that paramount chief election 35 years ago.

Thirty-five years in service, but in no way is Chief Caulker retiring. He seems to just be picking up speed, with plans for the coming years pouring out.

Thirty-five years in service, but in no way is Chief Caulker retiring. He seems to just be picking up speed, with plans for the coming years pouring out.

School sports meets are a huge deal across Sierra Leone, but especially in rural towns like Rotifunk with little to entertain and amuse. Students march onto the sports field in brightly colored T-shirts for their house’s color, while a DJ blasts out music with massive speakers (thanks to a generator for power).

School sports meets are a huge deal across Sierra Leone, but especially in rural towns like Rotifunk with little to entertain and amuse. Students march onto the sports field in brightly colored T-shirts for their house’s color, while a DJ blasts out music with massive speakers (thanks to a generator for power). Announcers calls out the competitors in their various track & field events and give the volleyball play-by-play account. Winners in individual events get certificates. Houses will parade around town with trophies boasting of their overall meet results.

Announcers calls out the competitors in their various track & field events and give the volleyball play-by-play account. Winners in individual events get certificates. Houses will parade around town with trophies boasting of their overall meet results. My colleagues from our partner CCET-SL turned out to support Arlene’s house. Each house comes with its own masked “devil,” a nod to their traditional societies. These devils compete in a wildly gyrating dance competition where spectators vote by tossing money in their basket.

My colleagues from our partner CCET-SL turned out to support Arlene’s house. Each house comes with its own masked “devil,” a nod to their traditional societies. These devils compete in a wildly gyrating dance competition where spectators vote by tossing money in their basket.

Junneth grows sweet potatoes, (left), corn, yams and eggplant to eat and to sell in the market for money to live on. You’ll see her in a nearby river after school catching fish to eat.

Junneth grows sweet potatoes, (left), corn, yams and eggplant to eat and to sell in the market for money to live on. You’ll see her in a nearby river after school catching fish to eat.  She explained, an educated woman can work and improve the community. People respect her. Men respect her. When a woman can earn a living and help the family, it helps her marriage. She said, “If I learn, I also [will] have something. He will give; I will also give.” A two-career couple is needed in Sierra Leone to move away from subsistence farming to a more middle class life, just as much as it’s needed in the US.

She explained, an educated woman can work and improve the community. People respect her. Men respect her. When a woman can earn a living and help the family, it helps her marriage. She said, “If I learn, I also [will] have something. He will give; I will also give.” A two-career couple is needed in Sierra Leone to move away from subsistence farming to a more middle class life, just as much as it’s needed in the US. Mrs. Kaimbay arranged a scholarship, asked Bumpeh Academy to enroll Junneth in school and gave her a uniform. She became a proud 10th grade student, in her first year of senior high, picking up where she left off years before.

Mrs. Kaimbay arranged a scholarship, asked Bumpeh Academy to enroll Junneth in school and gave her a uniform. She became a proud 10th grade student, in her first year of senior high, picking up where she left off years before.

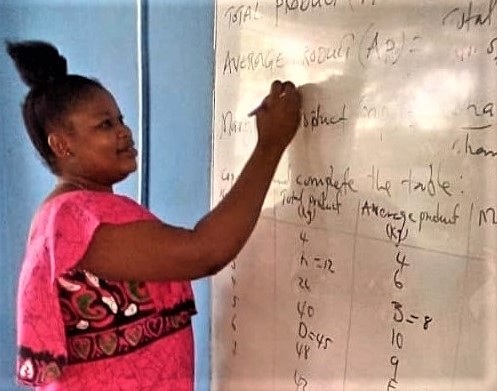

She’s brought the most qualified local teachers together to provide evening classes that complete and intensively review the school curriculum. 9th graders in schools without qualified teachers now get the chance to be fully prepared for their national proficiency exam.

She’s brought the most qualified local teachers together to provide evening classes that complete and intensively review the school curriculum. 9th graders in schools without qualified teachers now get the chance to be fully prepared for their national proficiency exam. Mrs. Kaimbay is focused on the success of the chiefdom’s teens.

Mrs. Kaimbay is focused on the success of the chiefdom’s teens.

CCET-SL grows orange, lime, grapefruit, African plum, cashew, avocado, guava and coconuts, all with seed they collect from locally purchased fruit.

CCET-SL grows orange, lime, grapefruit, African plum, cashew, avocado, guava and coconuts, all with seed they collect from locally purchased fruit.

CCET-SL grows some specialty trees like African plums, left.

CCET-SL grows some specialty trees like African plums, left.

Village beginning Aminata, left, is the youngest of 12 children. Her parents scratched together a living in the Rotifunk area. It’s typical of the chiefdom, with mud houses and where most earn a dollar or two a day as small traders at the weekly market. Her father was a primary school teacher, a low paying job, and her mother a trader. Now, her father is retired and her mother blind.

Village beginning Aminata, left, is the youngest of 12 children. Her parents scratched together a living in the Rotifunk area. It’s typical of the chiefdom, with mud houses and where most earn a dollar or two a day as small traders at the weekly market. Her father was a primary school teacher, a low paying job, and her mother a trader. Now, her father is retired and her mother blind. Proud college student Aminata, left, is now a first year student at the Institute of Public Administration and Management at the University of Sierra Leone in Freetown – thanks to Sherbro Foundation’s first college scholarship award of $1700, paying her first year’s tuition, fees, books, transportation and a stipend for living expenses.

Proud college student Aminata, left, is now a first year student at the Institute of Public Administration and Management at the University of Sierra Leone in Freetown – thanks to Sherbro Foundation’s first college scholarship award of $1700, paying her first year’s tuition, fees, books, transportation and a stipend for living expenses. “She is a woman, but she does [so much] good and all the people in the community admire her,” Aminata said. Rosaline shows girls a woman born in their chiefdom can get a college degree and take leadership roles usually filled by men.

“She is a woman, but she does [so much] good and all the people in the community admire her,” Aminata said. Rosaline shows girls a woman born in their chiefdom can get a college degree and take leadership roles usually filled by men.

Alima, left, is one student who signed up. We

Alima, left, is one student who signed up. We  Thanks to a $5,000 Beaman Family Fund grant, the Tutoring Program is being offered free of charge to both girls and boys.

Thanks to a $5,000 Beaman Family Fund grant, the Tutoring Program is being offered free of charge to both girls and boys. Paramount Chief Charles Caulker visited the first week and immediately called us in Cincinnati. We heard all the noise in the background of kids getting into the preloaded computer games, as their first effort in learning how to navigate a PC and use the mouse. He said it made him so proud.

Paramount Chief Charles Caulker visited the first week and immediately called us in Cincinnati. We heard all the noise in the background of kids getting into the preloaded computer games, as their first effort in learning how to navigate a PC and use the mouse. He said it made him so proud. Students don’t have textbooks and must copy limited notes teachers write on the blackboard.

Students don’t have textbooks and must copy limited notes teachers write on the blackboard. Working to fill this gap is CCET-SL’s Tutoring Program, the brainchild of Managing Director Rosaline Kaimbay, left. As a former school principal, she ran year-end study camps where 9th graders had intensive all-day review classes for four weeks. The result was 100% of her students passed the junior high BECE completion exam, uncommon for any school, let alone a rural school.

Working to fill this gap is CCET-SL’s Tutoring Program, the brainchild of Managing Director Rosaline Kaimbay, left. As a former school principal, she ran year-end study camps where 9th graders had intensive all-day review classes for four weeks. The result was 100% of her students passed the junior high BECE completion exam, uncommon for any school, let alone a rural school. Girls like Adama, left, feel pride that they’re joining a group of chiefdom academic elites, studying with the best local teachers in a first-class environment complete with solar light and computers.

Girls like Adama, left, feel pride that they’re joining a group of chiefdom academic elites, studying with the best local teachers in a first-class environment complete with solar light and computers. It’s too far for them to walk home from school for their main (and sometimes only) daily meal and return again for evening classes. Some had not eaten since heading to school at 7 a.m.! And it’s too dark for girls to be walking home that distance at 7:30 p.m.

It’s too far for them to walk home from school for their main (and sometimes only) daily meal and return again for evening classes. Some had not eaten since heading to school at 7 a.m.! And it’s too dark for girls to be walking home that distance at 7:30 p.m.