Alima just finished 8th grade. She’s a spirited 13-year-old who speaks right up, but she’s small for her age. It was only after I asked in our second conversation that she told me she walks to school from her village six miles away.

That’s 12 miles a day to and fro, every day. But Alima has a scholarship and is happy to be in school. I could tell she’s bright, which her vice principal confirmed.

That’s 12 miles a day to and fro, every day. But Alima has a scholarship and is happy to be in school. I could tell she’s bright, which her vice principal confirmed.

13-year-old Alima, left, student at Bumpeh Academy with Arlene Golembiewski, SFSL

Girls must grow up early when they decide to go to secondary school in Bumpeh Chiefdom, Sierra Leone.

They have huge hurdles to pass for the basic education westerners take for granted.

It starts with getting to a school.

Alima is not alone in walking a long way to school. It’s common for village girls to walk 4, 5, 6, even 7 miles each way to Rotifunk schools every day. Leaving when dawn is just breaking, kids begin their long trek, often on an empty stomach. Their return trip is under the hot tropical sun.

Bumpeh Chiefdom is made up of 200 small villages of 200 to 400 people, sprinkled throughout the chiefdom. Most are too small to support a primary school, let alone a junior high or high school. Girls must go to Rotifunk, the chiefdom seat, to attend one of four secondary schools of different types and faiths. A new junior high recently opened in a larger village. It’s struggling with funding and getting teachers who have training beyond high school themselves.

Bumpeh Chiefdom is made up of 200 small villages of 200 to 400 people, sprinkled throughout the chiefdom. Most are too small to support a primary school, let alone a junior high or high school. Girls must go to Rotifunk, the chiefdom seat, to attend one of four secondary schools of different types and faiths. A new junior high recently opened in a larger village. It’s struggling with funding and getting teachers who have training beyond high school themselves.

Only a couple rickety, well-used mini-vans travel the dirt back roads as public transportation, and only a few times a week, usually for market days. They’re not out in the early dawn hours to reach school for 8 o’clock assembly.

Kids like Alima can’t afford to pay for daily transportation anyway. They walk every day. Many miles.

Village girls have to leave home to board with a family in Rotifunk or a nearby village.

Alima lives with her aunt in Mokebi village. She’s typical of girls who must leave their parents and home at an early age to go to school. If they’re fortunate like Alima, they board with a family member who can offer housing and some level of family life. If better off, the relative may even pay the child’s school fees.

Alima lives with her aunt in Mokebi village. She’s typical of girls who must leave their parents and home at an early age to go to school. If they’re fortunate like Alima, they board with a family member who can offer housing and some level of family life. If better off, the relative may even pay the child’s school fees.

Split families are common in Sierra Leone. Husbands and wives work in different places. Alima’s parents are older and couldn’t pay for any more schooling, so they sent her to her aunt. Single parents and poor families often can no longer afford to feed teenage children, and send them to relatives. Family members are left to take in orphans.

When asked who girls live with, the answer so often is, my aunt. Rotifunk is a local trading center with a large weekly market, smaller daily markets and other places to sell, like school lunch stands. Market trading and cooking and selling food are the domain of women. They’re often single heads of households, their men gone or looking for jobs in larger towns and cities. Little money finds its way back home. But women keep taking in children and find ways to stretch their tiny incomes.

When asked who girls live with, the answer so often is, my aunt. Rotifunk is a local trading center with a large weekly market, smaller daily markets and other places to sell, like school lunch stands. Market trading and cooking and selling food are the domain of women. They’re often single heads of households, their men gone or looking for jobs in larger towns and cities. Little money finds its way back home. But women keep taking in children and find ways to stretch their tiny incomes.

Isatu B. was recently orphaned. “I no longer have any strong relative who will help me go through schooling,” she said. Relatives strapped for money and with children of their own may offer girls little more than a place to sleep. Teens away from home for the first time can get little supervision. At 15 and 16 years of age, many are making their own way.

Girls work for a living while going to school.

After a day at school and walking 12 miles, Alima helps her farmer aunt planting and weeding the cassava, yams and okra they grow. This is their livelihood and pays for their food and her school uniform.

Girls take on many physical chores after school. They’re cooking on wood fires, doing laundry by hand, carrying water and fetching firewood. They work on family farms, and may be selling its produce or other goods in the local market after school.

If girls can’t rely on a guardian for money, they have to earn the money for their daily food and school expenses (school fees, uniform and school supplies).

If girls can’t rely on a guardian for money, they have to earn the money for their daily food and school expenses (school fees, uniform and school supplies).

Their family or guardian may advance them $10 to sell things in the market. They buy elsewhere and resell in Rotifunk at a higher price. Or they make fried doughnuts or cakes to sell, or bring produce from the family farm. It’s painstaking work, clearing cents on the dollar.

Girls spend their school vacations working to clear enough profit to buy a $15 school uniform they’ll wear for the year.

When these girls leave home and work to earn money for school, it’s not unlike young adults in the US going to college. But these girls may start at the age of 12. They’ll work their way through six years of school before they can think about vocational training or college – which costs even more.

When a girl receives a scholarship and a school uniform, it frees her to focus on her studies. Isatu K. lives with her grandmother and said she no longer has the fear of being asked out of class to go home for school fees. It gives her a sense of security.

When a girl receives a scholarship and a school uniform, it frees her to focus on her studies. Isatu K. lives with her grandmother and said she no longer has the fear of being asked out of class to go home for school fees. It gives her a sense of security.

Schools depend on school fees for operating costs. During the school year, students who can’t pay the term’s fees have to leave and try to come up with the money. It’s humiliating and children feel rejected at this young age. With no money, they may have to drop out of school and repeat the grade next year.

A scholarship and a paid school uniform don’t just give a girl the chance to progress through school. They give her the self-esteem to be a success.

She’ll work less. And get back her childhood.

Staying in school, she has a future.

For $17, you can keep a girl like Alima in school for the whole year with a scholarship. $35 pays for a scholarship and a school uniform.

Open up her world. Click here: I want to send a girl to school.

Yet Isatu has big plans. She wants to become a lawyer.

Yet Isatu has big plans. She wants to become a lawyer. As a biologist myself, I had to stop and think, it’s the same as with any other fruit. In nature fruit drops from a tree and will start growing where it falls.

As a biologist myself, I had to stop and think, it’s the same as with any other fruit. In nature fruit drops from a tree and will start growing where it falls. Bumpeh Chiefdom is lowland tropical rainforest, perfect for growing coconuts. The Center for Community Empowerment & Transformation (CCET) is growing them commercially by the hundreds in a coconut nursery.

Bumpeh Chiefdom is lowland tropical rainforest, perfect for growing coconuts. The Center for Community Empowerment & Transformation (CCET) is growing them commercially by the hundreds in a coconut nursery. Coconuts, shell and all, are planted about a third of the way into loose soil and covered with straw mulch.

Coconuts, shell and all, are planted about a third of the way into loose soil and covered with straw mulch. CCET’s nursery manager, Pa Willie, grows project coconuts in a protected nursery to keep thieves from stealing them. It’s a fenced in and locked pen right behind his house he keeps an eye on.

CCET’s nursery manager, Pa Willie, grows project coconuts in a protected nursery to keep thieves from stealing them. It’s a fenced in and locked pen right behind his house he keeps an eye on. Work is underway and on a tight schedule, as the annual rains started in May. Here’s the step by step process.

Work is underway and on a tight schedule, as the annual rains started in May. Here’s the step by step process.

With no mechanized equipment to clear the land, it must be burned.

With no mechanized equipment to clear the land, it must be burned.

Little goes to waste in Bumpeh Chiefdom.

Little goes to waste in Bumpeh Chiefdom.

A partnership between Ann Arbor Rotary and the Freetown Rotary Club in Sierra Leone will oversee the project’s progress.

A partnership between Ann Arbor Rotary and the Freetown Rotary Club in Sierra Leone will oversee the project’s progress.

I have two visual barometers for the Salone economy. Freetown’s beaches were empty. No tourists, which adds to unemployment. People can’t afford to go to their own gorgeous beaches.

I have two visual barometers for the Salone economy. Freetown’s beaches were empty. No tourists, which adds to unemployment. People can’t afford to go to their own gorgeous beaches.

This mother of twelve shows us it’s never too late to learn your ABCs for the first time, and how to “carry over” when adding three digit numbers.

This mother of twelve shows us it’s never too late to learn your ABCs for the first time, and how to “carry over” when adding three digit numbers.

For Bumpeh Academy, one of the Chiefdom’s newer schools, progress happens in small steps. Very small steps. Senior high classes, previously run “second shift” in a primary school, moved to the main school addition, still in progress as funds are available. In 2015, a concrete slab was poured for three classrooms. In 2016, a zinc roof and partial walls between rooms were added, and classes started. I was happy to hear from Vice Principal Koroma, above, SFSL funded part of the addition with the school fee scholarships we paid for girls. They used the money to buy bags of concrete. Still, children at Bumpeh Academy are in school learning. 98% of Academy students taking the 2016 senior high entrance exam passed! And they have a new Peace Corps teacher, Ethan Davies, above, right corner.

For Bumpeh Academy, one of the Chiefdom’s newer schools, progress happens in small steps. Very small steps. Senior high classes, previously run “second shift” in a primary school, moved to the main school addition, still in progress as funds are available. In 2015, a concrete slab was poured for three classrooms. In 2016, a zinc roof and partial walls between rooms were added, and classes started. I was happy to hear from Vice Principal Koroma, above, SFSL funded part of the addition with the school fee scholarships we paid for girls. They used the money to buy bags of concrete. Still, children at Bumpeh Academy are in school learning. 98% of Academy students taking the 2016 senior high entrance exam passed! And they have a new Peace Corps teacher, Ethan Davies, above, right corner.

In full swing, CCET’s fruit tree nursery grows a variety of trees from seed: orange, grapefruit, lime, avocado, guava, cashew, mango. Three workers plant seeds collected from local fruit, and water and nurse them for a year+ until ready to plant in the Village Orchard program. Some go to newborn parents, restoring the tradition of “baby trees.” Some will be sold for income to continue to operate the nursery. Abdul learned to write and make signs in Adult Literacy class.

In full swing, CCET’s fruit tree nursery grows a variety of trees from seed: orange, grapefruit, lime, avocado, guava, cashew, mango. Three workers plant seeds collected from local fruit, and water and nurse them for a year+ until ready to plant in the Village Orchard program. Some go to newborn parents, restoring the tradition of “baby trees.” Some will be sold for income to continue to operate the nursery. Abdul learned to write and make signs in Adult Literacy class.

Bumpeh Chiefdom is a prime coconut growing area. Pa Willie personally raises coconut seedlings in a closed pen behind his house to keep out thieves. The coconut, husk, shell and all, is embedded in soil until it sprouts. It’s a longer-term venture taking two years, but they’re worth more. Pa Willie’s tree-growing skills date back to working in a Liberian rubber plantation before the war.

Bumpeh Chiefdom is a prime coconut growing area. Pa Willie personally raises coconut seedlings in a closed pen behind his house to keep out thieves. The coconut, husk, shell and all, is embedded in soil until it sprouts. It’s a longer-term venture taking two years, but they’re worth more. Pa Willie’s tree-growing skills date back to working in a Liberian rubber plantation before the war.

Sherbro Foundation Executive Director and P&G Alumna Arlene Golembiewski, left with Sulaiman Timbo, submitted the proposal. S

Sherbro Foundation Executive Director and P&G Alumna Arlene Golembiewski, left with Sulaiman Timbo, submitted the proposal. S High school students like Zainab, left, get practical

High school students like Zainab, left, get practical  Adults develop

Adults develop  The Center itself is a new

The Center itself is a new

Mr. Bendu, a primary school head-teacher, came into the new printing service at the Center for Community Empowerment & Transformation (CCET) to get some UN Children’s Feeding Program forms printed. He walked out of the new Community Computer Center 20 minutes later with his copies.

Mr. Bendu, a primary school head-teacher, came into the new printing service at the Center for Community Empowerment & Transformation (CCET) to get some UN Children’s Feeding Program forms printed. He walked out of the new Community Computer Center 20 minutes later with his copies. CCET’s new printing service in Rotifunk is scoring a home run for their customers and for themselves.

CCET’s new printing service in Rotifunk is scoring a home run for their customers and for themselves.

Only four months earlier, to get anything printed Mr. Bendu faced an all-day or an overnight trip to the capital, crammed into a minivan bus or on the back of a motorcycle taxi on treacherous roads. His transportation costs alone would have been 10 to 20 times the cost of the printing. The time wasted is just accepted, a common inefficiency holding back developing countries like Sierra Leone.

Only four months earlier, to get anything printed Mr. Bendu faced an all-day or an overnight trip to the capital, crammed into a minivan bus or on the back of a motorcycle taxi on treacherous roads. His transportation costs alone would have been 10 to 20 times the cost of the printing. The time wasted is just accepted, a common inefficiency holding back developing countries like Sierra Leone. These three grant makers were happy to invest in projects giving this rural community services they never had before, knowing income goes to support nonprofit programs.

These three grant makers were happy to invest in projects giving this rural community services they never had before, knowing income goes to support nonprofit programs. Sulaiman Timbo, left, and below left, is printing service and IT manager

Sulaiman Timbo, left, and below left, is printing service and IT manager Cell phones are now a way of life, and this means daily charging in a rural town with no electricity.

Cell phones are now a way of life, and this means daily charging in a rural town with no electricity. The CCET Center rents meeting and workshop space for NGO and government programs during the day, when no classes are in session. It’s the only place in town and for miles around with a facility to hold professional meetings for 20 to 100 people.

The CCET Center rents meeting and workshop space for NGO and government programs during the day, when no classes are in session. It’s the only place in town and for miles around with a facility to hold professional meetings for 20 to 100 people. Next on the list to introduce is a small canteen for cold drinks, snacks and catered meals. The room next to the main hall, left, is ready.

Next on the list to introduce is a small canteen for cold drinks, snacks and catered meals. The room next to the main hall, left, is ready. There’s also a growing need for internet service. People may not own their own computer, but they want to be connected to the world around them by email and Facebook.

There’s also a growing need for internet service. People may not own their own computer, but they want to be connected to the world around them by email and Facebook.

Some like Alima Kanu, left, JSS II (8th grade), are the oldest and first child in their family to go to secondary school. She comes from a small village where her parents are rice farmers. Her scholarship to Bumpeh Academy made the difference in her continuing in secondary school.

Some like Alima Kanu, left, JSS II (8th grade), are the oldest and first child in their family to go to secondary school. She comes from a small village where her parents are rice farmers. Her scholarship to Bumpeh Academy made the difference in her continuing in secondary school. With her scholarship, Isatu Kargbo, left, completed JSS III (9th grade) and got the highest result of 127 students taking the senior high entrance exam.

With her scholarship, Isatu Kargbo, left, completed JSS III (9th grade) and got the highest result of 127 students taking the senior high entrance exam. Sherbro Foundation supports five Bumpeh Chiefdom secondary schools of all faiths with scholarships. I met with the 50 girls at Ahmadiyya Islamic Secondary School receiving scholarships this academic year.

Sherbro Foundation supports five Bumpeh Chiefdom secondary schools of all faiths with scholarships. I met with the 50 girls at Ahmadiyya Islamic Secondary School receiving scholarships this academic year. She went on to talk about the challenges the girls face in going to school. There are 208 villages in the chiefdom and only five secondary schools. Many girls must walk 4 or 5 miles or more each way to reach one of schools, often making them late for class. And the tropical sun is hot walking home on an empty stomach to get their one meal of the day.

She went on to talk about the challenges the girls face in going to school. There are 208 villages in the chiefdom and only five secondary schools. Many girls must walk 4 or 5 miles or more each way to reach one of schools, often making them late for class. And the tropical sun is hot walking home on an empty stomach to get their one meal of the day. Kadiatu, left, told me most girls have no lights at home and have difficulty studying at night. By the time they get home and do chores, it’s dark. At the equator, it’s dark by 7 p.m. year-round.

Kadiatu, left, told me most girls have no lights at home and have difficulty studying at night. By the time they get home and do chores, it’s dark. At the equator, it’s dark by 7 p.m. year-round.

Rice farmers are often forced to take a loan from a local lender at interest rates of 50% and more to send their children to school. These informal village lenders can charge this much because villagers usually have no other option for a loan.

Rice farmers are often forced to take a loan from a local lender at interest rates of 50% and more to send their children to school. These informal village lenders can charge this much because villagers usually have no other option for a loan.

Fula Musa was one of eight women in the project from this small village of 25 houses.

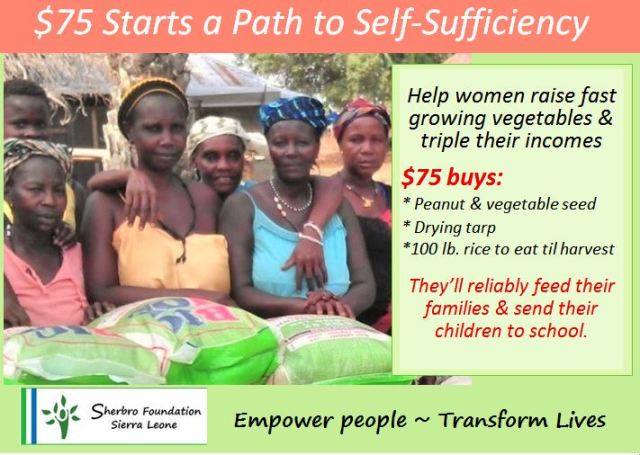

Fula Musa was one of eight women in the project from this small village of 25 houses. Bumpeh Chiefdom women work hard to make little money.

Bumpeh Chiefdom women work hard to make little money.

Give for Good

Give for Good

Growing peanuts and other vegetables helps diversify crops and reduces risk for these subsistence farmers.

Growing peanuts and other vegetables helps diversify crops and reduces risk for these subsistence farmers. Research around the world has shown that women spend most of their income locally, helping build the local economy and small businesses. This strengthens their communities.

Research around the world has shown that women spend most of their income locally, helping build the local economy and small businesses. This strengthens their communities.